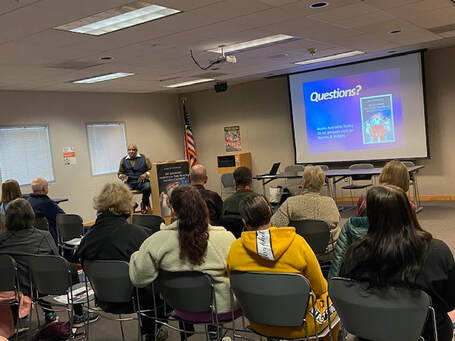

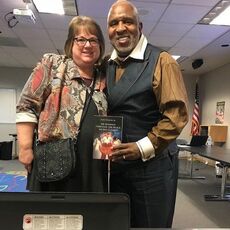

By Denise Stripes On the 29th of February, 2020, James Wilburn released his book, My Journey through the Black Sacred Cosmos, at the South Hill Library in Spokane, Washington. The first thing that Wilburn said, talking about his book, is “My book is not very wordy.” Reading the book, however, I was struck by the depth that can be found in a book that isn’t terribly “wordy.” Wilburn’s book is profound, and rife with paradox. When you meet James Wilburn, you encounter a kind, gentle, intelligent man, whose passion is for education—specifically, for ameliorating the racial inequalities that stem from the Eurocentric perspective in our public education system. But Wilburn’s childhood was steeped in a culture of unkindness, brutality, and the ignorance of those who would oppress people based on their skin color. Even his name becomes a paradox, because the name Wilburn came from people who owned Wilburn’s family, not from the family’s own rich heritage. When asked about this name, and how it affects him, Wilburn told how he keeps the name because it’s known, which is important for a person whose work is in the public eye. Thus, the name that was a slave name for his ancestors now represents Wilburn’s own work and livelihood. Wilburn, however, also has an African name, Adé Kunlé, which means “A Royal King (Adé) Fills Our Home With Honor (Kunlé).” Speaking of Wilburn’s African name, Dr. Nkosi Ajanaku, from the Future America Basic Research Institute, told Wilburn that he gave him that name because when he visited him, he filled his home with honor. Wilburn shared with his listeners some of the stories from his childhood that he includes in his book, ranging from interesting stories such as when his father would take James—aged ten or eleven years at the time—and his brother—age nine or ten—to Heck’s Service Station, where the two would do the hambone to earn some money for snacks, to heartbreaking accounts like when his father’s hotel was burned to the ground. But perhaps the most profound aspect of the book is found in the title itself, and what the Black Sacred Cosmos meant to Wilburn, as a child, and now, as an advocate for learning. In his book, Wilburn relates that “[g]rowing up entirely in an African American society leaves me void of any European American sacred experience. My experience growing up in the Jim Crow south leaves me void of any European American Faith-based ideology” (3). Talking to those of us at his book release, he expounded that children can grow up in the same community, attend the same church and the same schools, but see the world very differently. For Wilburn, the Black Sacred Cosmos “has everything to do with my sacred journey,” and his community at Sunset in Arkansas provided a haven, a shelter for the children from the oppression of the Jim Crow south, even if they could not shelter Wilburn and his siblings from the worst of the violence. In addition to this haven, his community provided the education he needed to “know and love himself,” so that “he could better understand and love others,” as stated in his biography on the book cover. Wilburn’s hope is to bring this message to children today, who, he says, need to learn the lesson much faster than he did as a child. Along with that hope, the book brings a message to the wider world, and, for me, is a source of insight into a time and a situation that history books cannot convey to those of us who not only never lived such a life, but have no cultural or familial context of our own to help us understand. Wilburn’s story is important, even though it isn’t wordy, not only for those whose ancestors lived its reality, but for all of us who can benefit from the insight of Wilburn’s Black Sacred Cosmos.

0 Comments

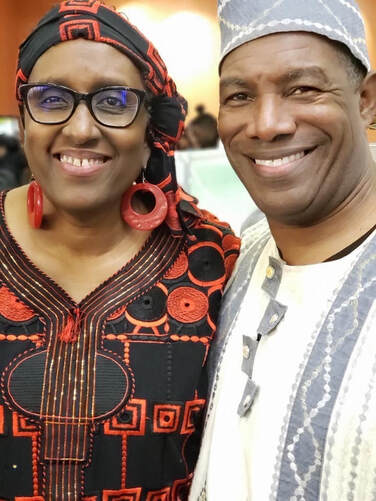

\ By Denise Stripes for Wilburn & Associates On 29 December, 2019, Wilburn and Associates, in conjunction with North-west Winterfest, held their second annual Kwanzaa Celebration, immersing a corner of Spokane’s Northtown Mall in the beauty of African culture. The area was tucked away from the mall traffic, and the décor—as well as the aromas of the foods crafted by local vendors—offered a warm and intimate setting rather than the sterile environment one would expect in a mall. The walls were painted in warm colors and graced with beautiful African art. Just behind the dais, a small tapestry presented a village scene, with palms and other trees, a hut, and people working under the sun—a representation of community, the central theme of Kwanzaa. On the dais, two chairs presided, anticipating the arrival of the Kwanzaa King and Queen; at their side, African djembe awaited their cue to provide the musical backdrop for the celebration. Just before the dais stood the kinara, a holder for the mishumaa saba, the seven candles. The gathering of spectators included people from a medley of ethnicities who came to share in the festival, which illuminated, for those of us without a clue, the meaning and spirit of Kwanzaa. The observance began with some ceremony; we stood as James and Roberta Wilburn heralded with drums the arrival of the Kwanzaa Queen, Stephy Nobles Beans, and the Kwanzaa King, Cecil Jackson. When the Queen and King were seated, James Wilburn signaled with the drum the beginning of the offering of libations. Roberta Wilburn later explained to me the meaning of this tradition, asserting that, while she would not normally cite Wikipedia, it actually gives a good definition for libations: “In African cultures […], the ritual [generally performed by an elder] of pouring libation is an essential ceremonial tradition and a way of giving homage to the ancestors. […] A prayer is offered in the form of libations, calling the ancestors to attend.” To put this African tradition into the context of the African-American celebration, James Wilburn adds, “Libations is contributing your being and success to those who sacrificed for you being here. Libations are done in threes because three is the biblical number of completion. You pay libation three times, recalling what your ancestors did that made it possible for you to do or be able to do the things you want to do.” In the course of the ceremony, James honored those who struggled and survived, citing several key events, in three stages, and pouring libations for each stage. The first period represented the struggle for freedom, and spanned from the first Africans who arrived in 1619 off the Virginia Coast and were made slaves to the abolishment of slavery in 1835. It is important to note that these first arrivals did not come here as slaves; they were poets, royalty, fathers, mothers, elders, and citizens from all walks of life, who lived in freedom and dignity, but had that stripped from them. Forced into slavery, they were not, in and of themselves, slaves. The second stage represented the struggle for citizenship and equal rights; Wilburn cited the 1868 ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which finally recognized the inherent rights of the freed people to equality and citizenship. The third stage gave homage to those who struggled for the right to vote, citing the 1870 ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, which implemented the right of African-American men to vote, and the securing of the right for women to vote in 1920. After the libations were offered, Roberta Wilburn gave a brief history of Kwanzaa, explaining the symbols, the seven principles, and the colors. Kwanzaa is a seven-day celebration, not a religious festival, but an homage to family, culture, and community. The seven days of Kwanzaa exemplify the seven principles: Umoja, Unity in the family, community, nation, and race; Kujichagulia, Self-Determination, that the people will define, name, create for, and speak for themselves; Ujima, Collective Work and Responsibility, to build and maintain the community; Ujamaa, Cooperative Economics, to build and maintain the community’s businesses; Nia, purpose, to build the community in order to restore the people to their traditional greatness; Kuumba, Creativity, to leave the community more beautiful and beneficial than they inherited it; and Imani, Faith, to believe in the people, and in the righteousness and victory of their struggle. The kinara holds the mishumaa saba, the seven candles that light the way, presented in three colors: three green candles for the land of Africa, three red for the blood that was shed in the struggle, and one black candle for the people, to show that black skin is not a badge of shame. On a mkeka, a mat representing the history, stands the kinara and the Kikombe chaumoja, the cup that represents unity; the mazao, or fruits and vegetables for the harvest; the muhindi, ears of corn that exemplify the children and the future; and zawadi, gifts for the children. Since 29 December marked the fourth day of Kwanzaa, JaNese Howard and Roberta Wilburn lit four of the candles on the kinara, and then Olynda Stone, in her beautiful voice, praised God, singing, “Lord I will lift my eyes to the Hills,” a powerful message from Psalm 121:1 about looking to God for help during hardships. While Kwanzaa celebrates community rather than religion, faith is an integral part of a community, another way to unite a people. This principle was also reflected in the performance from the Spokane Community Gospel Mass Choir. The ceremony continued with Gaye Hallman’s poem about the seven principles and how they work together, Mona Martin’s beautiful dance, James Wilburn’s drums, and Lillie Pirie, who read a children’s story called “The Feast.” Michael Bethely gave a poem titled “To You,” telling the beauty of the people: “You are imperfect, and that is flawless,” and JaNese Howard spoke from a teenage perspective, saying, “I stand here today as a strong black girl…It’s so important for me to know who I am and where I come from.” Howard concluded by proclaiming, “I am a queen; I am beautiful; I am worthy; I am Kwanzaa.” The Kwanzaa Queen, Stephy Nobles Beans, recited a poem extolling the beauty of the African countries, with the antiphon, “Way down in my soul.” With her many accomplishments here in the United States, her African roots remain in her soul, an inspiration to her and to those in her sphere of influence. Cecil Jackson, Kwanzaa King, who works with young people in track, as well as encouraging them to finish school, spoke of the graduation rates of young black people, stressing the importance of getting involved and being part of the solution. He also shed light on Kwanzaa’s fourth principle, speaking of the importance of a “co-op economy,” the keys to which are: first, supporting one another; second, strength in numbers; and third, faith in one another. Lastly, James Wilburn stressed the importance of those who lived through the atrocities of the past with the story of the djembe. These drums were used in Africa to communicate between people, tribes, and countries, and James told how the slaves would entertain their masters with the drums, all the while using the drums to communicate and free the people. They demonstrated the principle of striving and thriving, when the masters took the drums away, by tapping the same messages with their feet. One of an oppressor’s most insidious tools is to remove the means of communication from the oppressed. By maintaining communication through innovation, among other accomplishments, these men and women fought for the future of their people, and paved the way for all who persevered through the days of Jim Crow laws and the Ku Klux Klan, and for those who continue the struggle today, and who honor their forebears in the spirit of Kwanzaa. Courageous Conversations: Should America Pay Reparations for Slavery? I want to thank Denise Stripes for attending our last Courageous Conversations and capturing the essences of what took place. The following is her perspective of what transpired. Anyone who has read Toni Morrison’s Beloved has somewhat of an idea concerning the details of the Middle Passage and slavery but, if one has not experienced it, that idea is vague at best. Those whose ancestors experienced these things may have a better idea, though even their accounts are second-hand. Though some have done research that indicates the possibility that trauma from slavery has been passed on to the descendants of slaves, the argument, though cogent, is not conclusive. If, as the research suggests, the trauma has indeed been passed on, the question of whether America should pay reparations for slavery takes on a new layer of understanding. On 27 July, 2019, Wilburn and Associates hosted an opportunity for discussion on this subject. The discussion began with a presentation on the realities of slavery, followed by a panel discussion, and questions from the audience. The discussion was held in the Carl Maxey Center, and attended by over 40 people of diverse ethnicities. While the conversation was supposed to address whether or not America should pay reparations, the panel and the audience all agreed that we should. The lack of an opposing view left some questions unasked and unanswered, but the discussion was still lively, given that even those who agree that reparations should be paid have different ideas concerning how and to whom the restorations should be paid. The most prevalent question during the evening centered on who African Americans are. The opening presentation described the origins of the slaves who came from Africa, pointing out that they went from “Kings to Captives.” As Dr. Roberta Wilburn pointed out, “People were taken out of Africa and made into slaves.” Wilburn showcased the work of Dr. Joy DuGruy who, in her book Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing, gives a cogent argument for the idea that trauma resulting from slavery is passed from generation to generation. Wilburn also referenced Darrick Hamilton of Ohio State University, who posits that three areas of reparation need to be addressed: Acknowledgement, Restitution, and Reconciliation. While acknowledgement has begun in some circles, the panel and the attendants agreed that more must be done in this area. Restitution proves to be a logistical problem, though all agreed that it is necessary. As panel member Kiantha Duncan asserted, “America does not dismiss or excuse any other debt”; thus, this debt should not be excused either. Reconciliation seems to hinge on acknowledgement and restitution, but the problem remains: who decides what is enough, and how it should be done? None of these things can happen without communication, but communication is impossible until African Americans know who they are. This question posits a real and important conflict; as an audience member named Yashair Jones, pointed out, young African Americans don’t know who they are. Jones asserts that they know who they’re supposed to be; “…being a rapper, gangster, womanizer, drug abuser—that’s what I see when I look in the mirror—who I’m supposed to be,” and that “becomes the norm.” African American youth cannot relate to religion, because in church they see characters—a white Jesus, for example. Religion and culture offer no answers; thus, as Jones asserted, “we don’t know who we are [or] our value.” This conflict permeates all of African American culture, affecting education, housing, banking systems, and criminal justice, among many other issues. Panel member James Wilburn illustrated this problem by pointing out what he called “the difference between ‘Billy’ and ‘Jamal’.” Children are taught from a Euro-centric perspective, which addresses Billy’s culture, but not Jamal’s. This disparity seeps into all aspects of life, leaving African American youth wondering who they are. The question of “who we are” is only part of the problem, however. Among the panel members, while all agreed reparations should happen, the how and to whom became matters of contention. Several possible solutions were offered; for example, panel member Rosie Thurman suggested that those who made the money off the slave trade (e.g. tobacco companies, textile industries, etc.) should be taxed. Panel member Curtis Hampton, while holding that “this is not a one-prong issue,” and thus, not easy to answer, suggested that African American communities, not individuals, should receive the reparations, putting them into programs to help “make opportunities and strengthen families.” Hampton added that “People of color need to see people that look like them as teachers, police, and leaders.” Scott Ward, a history teacher at Ferris High School, suggested that reparations should involve a truth-seeking process, to include the correct telling of history and the removal of icons of the slave holders (which, in the broader conversation, will raise the question of free speech). Audience members also had suggestions; for example, Robert Lloyd suggested that the Gross National Product should be divided, and thirteen percent of that spent to advantage the Black population. Reconciliation will be a long road. Everyone agreed that, until African Americans can come together, this will not happen. Two questions from the audience touched on this issue: “Why don’t Black people in Spokane speak to each other?” and “Was American slavery related to the Bible?” Audience member Bayaah Jones related these two questions, saying that the Bible has been misused to justify slavery, but it actually explains it. However, Jones asserts, we don’t read it in context; thus, we miss the truth. Jones added that people can be brought together by the truth. Kiantha Duncan pointed out that African Americans are divided because “we have to compete for small bits of meat—we’re trying to survive.” Those who must compete to survive will find it difficult, if not impossible, to stand together. As Bayaah Jones pointed out, “Those who get reparations are nations of people; we [that is, African Americans] do not identify as a nation.” Thus, reconciliation must begin within the African American community, and then spread to the diverse community. In the evening’s final remarks, James Wilburn pointed out that the challenges are there; we need to know them and be prepared. Wilburn also said, “We need to teach our kids that they don’t come from slavery; they come from kings, mathematicians, philosophers, and leaders.” Wilburn’s statement echoed Kiantha Duncan’s, who suggested that practical solutions begin at home with ethnic studies—“teach your children.” Lastly, several of the panel members pointed out that one of the biggest tools available to bring about the needed changes is the vote, which includes education. Show up for these discussions, learn who represents you, and vote them in. This month we have a guest blog by Denise Stripes. She shares her thoughts on the second Courageous Conversation that Wilburn & Associates held at the West Central Community Center. I am sure you will enjoy reading what she gathered from the event. The term mass incarceration evokes images of crowds gathered behind bars, but the crowds are faceless, nameless, and dehumanized. When we speak of mass incarceration in the state or federal prison systems, the crowds are not only dehumanized, but they also bear the burden of being classified as criminals. The United States, which holds five percent of the world’s population, imprisons twenty-five percent of the world’s incarcerated population, and more than sixty percent of those imprisoned in the U.S. are people of color. For those of us outside the system, it is effortless to recline in our easy chairs, when hearing these words in the news or on social media, and dismiss the ramifications to those incarcerated by rationalizing that they are criminals, and they deserve what they get. Our consideration stops there, and we go on with our lives. Our complacency, however, carries the risk of making us unwittingly complicit in the injustices that affect the lives of those incarcerated, their families, and ultimately, our community as a whole. For this reason, events such as the conversation hosted on May 4 by Wilburn and Associates, “An Evening of Courageous Conversations: The School to Prison Pipeline and Mass Incarceration,” are not only important, but vital to our communities. This conversation consisted of a presentation by James Wilburn, followed by a panel discussion with eight panel members, all of whom have had some form of experience with the prison system. The event took place at West Central Community Center in Spokane, Washington, and the congenial air of the room, despite the seriousness of the issue, served to unite all present, even among those who disagree on issues. And these issues are important: how are young people getting pushed towards the prison system, even in school? What rights should incarcerated people have? What actually happens to people in the system, and how does it affect their families? Wilburn, in his presentation, gave us some facts, and some context. He defines the School to Prison Pipeline as “a nationwide system of policies that pushes students out of school and into criminal activity.” The push begins when students are disproportionately suspended and expelled due to factors such as race, ethnicity, and any kind of disability. For example, Wilburn reported that thirty-one percent of African-American students experience school-related arrests, and those who are suspended or expelled are three times more likely to encounter the criminal justice system within a year. Nationwide, approximately twice as many black students are expelled than white students. Wilburn then related some factors that contribute to the disparities among the students: teachers who do not use culturally sensitive response practices, developing instead an ineffective, one-size-fits-all response; zero tolerance policies for discipline; lack of alternatives for out-of-school suspensions; lack of evidence practices in dealing with discipline problems; and implicit biases/stereotypes as well as societal fears of African-American males. Wilburn explains the cultural differences between the casual feel of Spokane and those who come from segregated schools, and have had no preparation for dealing with other cultures. The language, dress, and mannerisms all differ from what such students have experienced, which leads to a feeling of dissociation. These factors contribute to a system that sets students up to fail. Wilburn quotes Fredrick Douglass, who said, “It’s easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.” Douglass’s words implore us to deal with the above-stated factors, as well as the system wherein students are policed rather than supported, in order to help more young people to lead free, productive lives, rather than falling into the abyss of mass incarceration. When Wilburn finished his presentation, the panel guests assembled, and suddenly, the faceless crowds we picture when we hear about mass incarceration became real people: Jermal Joe and his wife, Kym Joe, Jason Kiss, Virla Spencer, Duaa Rahemaah Williams, La Tasha Canto, Megan Pirie, and Portia Linear. It’s difficult to retain an air of complacency when speaking face-to-face with these folks. Some, such as Jason, Megan, Virla, and Jermal, have been incarcerated, while others, Kym, La Tasha, and Portia have family members who are or have been incarcerated. Several of the panelists now serve as advocates for prisoners’ rights. When asked what rights prisoners should maintain while incarcerated, practical issues such as the right to vote, while important to the panel, took a back seat to one overarching issue. Linear emphatically stated that those incarcerated should retain the right to their humanity. Linear stressed that prisoners are identified as numbers rather than as people, and are treated as less than human. Coming out of prison, these folks are still defined by others according to their crimes, rather than as human beings. As Kym Joe puts it, “That felony be fresh.” All of the panel members stressed that the system is not working like those of us on the outside think it is, although, in all honesty, those of us on the outside rarely think about how the system works for those on the inside, which is part of the problem. Wilburn asked the panel what rights should be restored when prisoners are released, and the panel first, and most importantly, emphasized the right to live. People who are defined by a past incarceration can face a daunting task in just finding a place to live, getting a job, and parenting their children. The system puts ridiculous obligations in their path, such as fees—sometimes thousands of dollars—that they must pay, classes they must take and pay for, because these classes are not offered in the system, drug treatment that must fit exacting criteria, and other unnecessary red-tape obligations that bog transitioning inmates down, and even lead to re-incarceration. Canto stresses that this re-incarceration is not because of new crime; rather it is because people violate the impossible barriers placed before them. As an example, Pirie is a drug counselor trainee, and is willing to help by teaching some of the classes required, but the Department of Corrections (DOC) will not let her teach because of her past incarceration. One of the most chilling assertions from the panel is that the system causes recidivism not because of mere oversight, but because the state makes money for incarcerating people. Kiss tells us that prisons get paid by bed-space, and so their primary goal is to keep the beds filled. Linear adds that children of previously incarcerated parents are six times more likely to be incarcerated, and that the way officials (law enforcement officials, school officials, etc.) speak to them discourages them from even trying. Linear relates that her nephew was told that “he will never get into college.” Canto asserts that the system is designed to protect white people, and Linear adds that the policies are designed specifically to oppress people of color and families of those incarcerated. Linear attends monthly meetings where these topics are discussed, but she relates that the attendants don’t take the problems seriously. An overarching question that was asked, but not overtly answered, concerns whether punishment works. In a system where prison is for profit, and where the incarcerated become numbers rather than people, one must wonder. And, if the punishment system doesn’t work, the question of solving the issue looms as well, because those who are dehumanized by the system have no outlet for change, and state officials, like Governor Jay Inslee, don’t see the need for a safe space for these folks to air their concerns. Canto related that those in the system are reluctant to approach the offices of those who incarcerate them, because that makes their lives more dangerous than they already are. Spencer spoke of a woman who, when violated by a corrections officer, filed a complaint, but the DOC, who feels no need to justify their actions, retaliated by sending her back to prison. The audience, during the Q & A, offered suggestions for improvement, but it seems that the roadblocks in place negate any of the possibilities. For example, one audience member suggested more panels such as this one, but Canto responded that the state will not sponsor panels with “lived experience” beyond the regional level, and that national conferences, which hold more influence, are limited to people who either have no experience, or who are part of the system. So, what can be done? While concrete answers were lacking, one member of the audience, Nicholas Sironka, suggested that the answer is “not to talk about how [the incarcerated] are there, but to talk about not having others join them.” Nicholas suggested think tanks, strategizing, and touching these individuals, and that “ripples will touch others.” Nicholas added, “Don’t scream, cry—find a solution…and those in prison, let them hear you are doing something.” At the end of the discussion, I had the opportunity to talk with Jermal Joe, who has been in prison for twenty-two years, since age seventeen, and who is transitioning out, and is partially incarcerated. I asked Jermal, if he could say anything to a world that would listen, what would he say? Jermal answered simply, “Second chances are very important.” His answer is poignant, and is a view that many people share. It touches on the complacency of those of us on the outside, who share this view, but don’t bother to know the real situation for people who are lost in the system. As Dr. Roberta Wilburn states, “We cannot let one mistake—or several mistakes—be the reason that we write people off.” It is time to get out of our easy chairs and attend these courageous conversations, because our voices, when combined with those who have lived experience, can help to make a difference.

For as long as I can remember, I have embraced my African roots. I’m not really sure where this came from. I was raised by my dad and he wasn’t accepting of his African ancestry or heritage. It was even a point of contention when I was in college and I wanted to wear my hair in an Afro. I was very much caught up with the message of James Brown’s song “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud.” I wanted to show my pride by wearing my hair natural and my dad was anything but pleased. He felt I was taking a step backward, and I think he was concerned about how I would be perceived in my prestigious, predominately white college. All of my life my dad always shared with me about what it meant to be a Black person in American society and the realities of discrimination and marginalization. However, he never demonstrated a connection with African culture. He was even rejecting of an African man that my sister was dating and made her give back gifts of African clothing. He never stated why he was so against our brothers and sisters from Africa but he made it very clear that he didn’t want to have anything to do with them and he wanted my sister and I to feel the same way. I suspect that his rejection of African culture was because he was like some Black people today who are still ignorant of their culture. They believe that our only connection with Africa is slavery and that is a part of our history they would like to forget. Many African Americans were never taught in school that slavery was only one episode in our history and that our African Ancestors were great kings, queens, mathematicians, and scholars. As I am often teaching about cultural competency, a frequent question that arises is what should we call people of African descent in America? Black or African American. I always encourage my students and workshop participants to ask people what they want to be called regardless of their race or ethnicity. I have heard Black people say, I’m not African American. I have no connection to Africa, I’m from Mississippi. Some vehemently deny they have anything to do with Africa. They know little or nothing about the continent, nor do they want to learn about it. It is very sad but it is directly related to the failing of our educational system that has sanitized history to make it more palatable to the majority population. There is an African proverb that states: “Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” This has been why so much of African/African American history and culture has been left out of our textbooks and the academic curriculum taught in our public schools/colleges. This makes it very difficult for African American people to know who they are, embrace their culture, and to be proud of their heritage. Several years ago, I came across a poem by Wayne Visser, I Am African, in a card and it immediately resonated with me. The beginning of the poem goes as follows: I am African Not because I was born in Africa But because Africa was born in me I am African Not because my skin is black But because my mind is empowered by Africa I am African Not because I live in Africa But because my soul is at home in Africa…. I would later adapt that poem and make it my own because it strongly reflected my sentiments toward Africa. It is who I am and it resonated with me even more after the first time I had an opportunity to visit the Motherland of Africa. All connections to our families of origin were lost when our African ancestors were stolen from their homeland, brought to this country, and taken from their parents. It made it impossible for us to really know who we are. Many of the other cultural groups do not have the same level of disconnection to their ancestry that African American people do. This significantly contributes to the lack of family cohesion that is so prevalent in the African American community today. We have to do a better job of educating everyone about African American history and culture but especially our children. Over the holidays one of our daughters gave my husband and I the gift of Ancestry DNA, something that we have both wanted for some time. James and I both anxiously awaited the results. I am pleased to say that after several decades, I finally know who I am. My results showed that I have a 54% ancestral connection to Cameroon, Congo and Bantu peoples with approximately a total of 72% ancestry from the continent of Africa. For many years I have been saying that even though I wasn’t born in Africa, that Africa was born in me. Now I know that I was right. I didn’t know it for sure but now I do. How comforting it is to know about my heritage and the foundation of my existence. With my new found knowledge, I will begin to search deeper into my family roots and when people ask me where I am from, I will proudly be able to tell them. Leave me a comment and tell me about what you know about your heritage. Do you know who you are? Do you know where your ancestors came from? Have you begun to explore your roots and your ancestry? If you have, what have you learned? What legacy do you want to leave your children and your grandchildren?

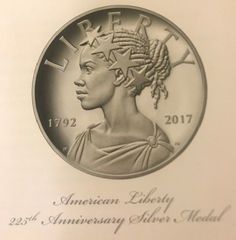

As I reflect upon the holiday season, I am reminded of a very special gift that I received last year from one of my faculty members. I have worked closely with this gentlemen for eleven and half years, but this gift caught me quite by surprise. I regularly give my staff and faculty Christmas gifts, but I don’t ever remember receiving a gift from this faculty member before. My curiosity was further peaked when he told me I couldn’t open it until Christmas day. That meant I had to wait approximately two weeks from the time he gave it to me. However, I was compliant, took it home, placed it under my Christmas tree, and waited. Although I am far from being a child, the unexpected gift made me more anxious than usual for Christmas to come that year. When I finally opened the gift on Christmas day, I was really surprised when I took the wrapping paper off, and it revealed a box that said “United States Mint, American Liberty 225th Anniversary Silver Medal.” It was too official for it to be a gag gift and given that it had a significant weight to it, I knew whatever was contained inside the box must be really special. Even though I had to go through several layers of official wrapping to finally get to the contents, I was not disappointed to say the least. My eyes were almost brought to tears when I saw, a silver coin representing Lady Liberty with cornrow braids and African American features. On April 2, 1792, the Senate and House of Representative enacted the Coinage Act which officially made such commemorations a reality. It had taken 225 years to have an African American woman represented on a liberty coin. However long it took for this recognition to occur, I am glad that it did. I do wonder how many people are aware of its existence. According to Mint designer Justin Kunz, “Introducing an African-American Lady Liberty underscores the diverse heritage of this Nation, and reminds us that liberty ought to be maintained for the rights and protection of all people without respect to race and ethnicity.”

Why was this gift so endearing to me? First, because my colleague and dear friend who gave it to me later told me that when he saw it, he had to get it for me because it represented who I was and the work that I have been doing. Second, this person also happens to be, a white male, who recognized and appreciated the years of dedication I have given to make our university a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive campus community. As an African American woman working in higher education for over 35 years, I know what it is like to be marginalized and discriminated against. However, it is not often that we are validated for the work that we do by our white colleagues, especially when it comes to diversity work. I do what I do because I am passionate about diversity and social justice, and not for recognition. Nevertheless, receiving this special gift, further validated my belief that not only is our work important but we are also making a visible difference that others are recognizing. This is why I am an inclusion practitioner and social justice advocate. This is one of the important “Whys” of my work. I believe that all people should be respected and valued regardless of their race, ethnicity or cultural background. If you would like assistance in supporting and growing your organization in the areas of diversity, please contact me at [email protected] for a free consultation to discuss how I can meet your diversity training, assessment, strategic planning, and coaching needs. Let me know what your WHYs are. What are the reasons you do the work you do? Have you faced challenges with diversity in the workplace? What have they been and how have you handled them? Looking forward to hearing your thoughts and comments below. |

AUTHORRoberta Wilburn is an Inclusion Practitioner with over 35 years of experience working in higher education, and as a consultant in public and private K-12 schools, government, non-profit and community based organizations. She has conducted diversity, equity, and inclusion training regionally, nationally, and internationally. She is the author of books, chapters, and journal articles. Her work has been recognized with local and national awards. Some of her awards include the 2017 Insight Into Diversity Giving Back Award for Administrators in Higher Education, the YWCA Women of Achievement Carl Maxey Racial and social Justice Award, and the Heartwood Award for Cultural Enrichment and Community Service.

ASSOCIATE BLOGGERDenise Stripes has lived in Spokane, Washington for twenty years. She is a wife of a veteran and has three adult children. She is also an adjunct English instructor at Spokane Community College. She earned her doctorate in English Literature from Washington State University. Above all, Denise is a committed believer in Jesus Christ, and wishes to see justice in her community as Christ would show it. She is a firm advocate of the Courageous Conversation, and is honored to write guest blogs about the events facilitated by Wilburn and Associates, LLC.

Archives

April 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed